20/20 Vision and beyond

By Steve Bee, VPS Group Commercial & Business Development Director

Twelve months ago, if the world’s population had the benefit of “20/20 vision”, would we have stopped the clocks, or chosen “fast-forward” to 2021? Without doubt the year 2020, has been one of the most challenging in terms of human health and business. Unfortunately shipping and the bunker industry have not escaped the health issues or the business downturn, in a year which was always going to raise its own specific challenges to the industry, in terms of the new IMO2020 legislation.

So, eleven months into 2020, what did we originally expect, what did we actually witness and what will the future hold for bunker fuel?

Prior to 2020 shipping companies faced the IMO2020 conundrum of which fuel would best suit their business needs, MGO, HSFO/Scrubbers, or the new VLSFOs which were coming into the market? Many experts predicted a huge increase in demand for MGO, whilst stating scrubber uptake had been slow and VLSFOs were relatively unknown in terms of performance.

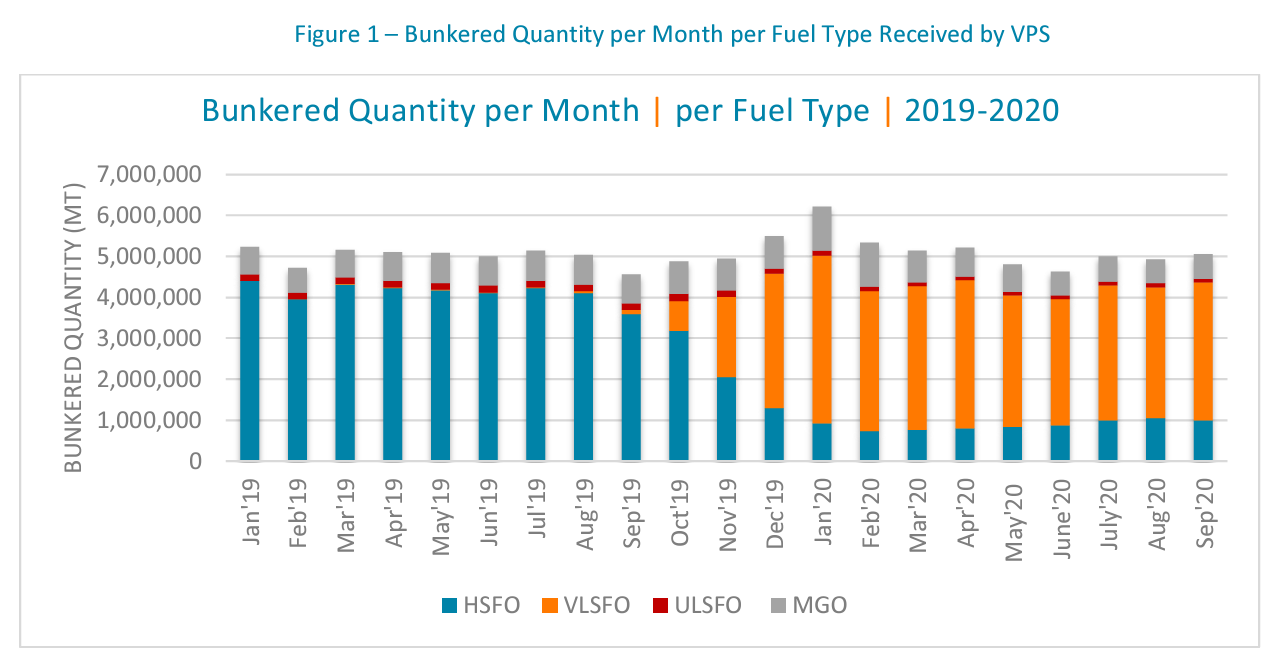

Whether it was for economic reasons, or other, the rise in demand for MGO never materialised and throughout 2020, MGO has accounted for only 12% of the samples received by VPS for testing.

With HSFO, historically the main bunker fuel of choice and accounting for 85% of all samples tested by VPS in 2019, this fuel immediately plummeted to only 15% in January 2020. However, between February 2020 to September 2020, HSFO samples grew by 37%, to account for 20% of all samples received by VPS, indicating an increase in scrubber usage as the year progressed.

VLSFO fuels were immediately taken up from just before January 2020 and have consistently accounted for 66% of all samples received by VPS, this year.

VLSFOs were forecast to be wide ranging in their viscosities and densities, be high in Cat-fines and to have stability and cold-flow issues, due to the higher paraffinic content and the interaction between the residual and distillate components of these highly blended fuels. This fuel type was most importantly to have a compliant sulphur content of 0.50% or less.

The reality of what we have seen in relation to VLSFOs is the density range has been proven to be wide ranging, although as the year has progressed, it has tightened a little and as of September 2020 ranged from 830-990kg/m3 , with 86% of all VLSFOs tested by VPS having a density between 920-980 kg/m3

As for viscosity of VLSFOs, the range has also been wide and up to September 2020, was 2Cst – 590Cst, but with 86% of all VLSFO viscosities being less than 180Cst. It is extremely rare to find a VLSFO at the 380Cst level.

If there has been one major repetitive occurrence with VLSFOs during 2020 it has been in relation to fuel stability. On many occasions, the fuel delivered to the ship has met specification, but within weeks the fuel has destabilised and formed sludges. The “shelf-life” of VLSFOs is less than three months, which is far less than HSFO (six months) and MGO (12 months). The complex blends of residual and paraffinic materials, has led to an almost conflicting situation, where VLSFOs require heating to avoid wax precipitating from the paraffinic content, but extended heating at higher temperatures, speeds up the fuel aging process and has a destabilising effect upon the residual components.

This links in to the cold-flow properties of VLSFOs, where at present 99% of VLSFOs have a Pour Point of less than 30°C, but 67% of VLSFO tested have a Wax Appearance Temperature (WAT) greater than 30°C, with the average WAT currently 21°C above the average pour point. Firstly, this would suggest that in many situations, the historical advice of storing fuel at +10°C above the pour point is no longer a safe recommendation, as wax may have already precipitated from the fuel at temperatures which are higher than +10°C of the pour point temperature.

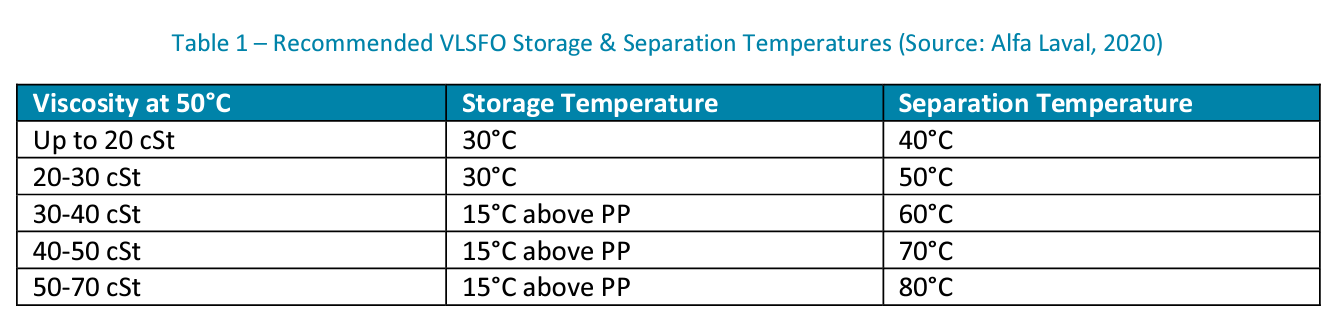

Secondly, separator OEMs generally recommend the temperatures mentioned in Table 1 for safely storing and separating VLSFOs. VPS has already observed several instances where the recommended separation temperature is below the WAT, which results in separator sludging or complete blockage, especially in cases where cat fines are high and viscosity is low. The problem of heating low viscosity fuel above the WAT is that the viscosity becomes so low that the booster pumps of the vessel cannot produce sufficient pressure, introducing leakages and potentially leading to vapour lock. When a vessel cannot increase the temperature above the WAT, due to operational restrictions, the fuel is essentially unusable.

During Q1-2020, VPS observed 40 cases where red and/or white deposits were found on piston tops, piston crowns and on the underside of cylinder heads (Figure 2). These deposits were often hard and required power tools to be removed. These deposits were linked to the excessive wear of cylinder liners, liner scuffing and broken piston rings. In the majority of cases, two-stroke engines were more susceptible to these types of damage.

This damage to engine components had a detrimental impact on vessel operability. The engines affected were not limited to any specific OEM, but from many of the major engine makers in the marine industry. In all cases VLSFO fuel quality was tested and found to be acceptable and the original cylinder oil that was used was grade 40BN supplied from most of the key suppliers.

The investigation identified that the reserve BN in the cylinder oil was not being utilised to neutralise the acids formed during the fuel combustion process as is its purpose. This resulted in calcium compounds being deposited on the piston top, which became hard and abrasive causing liner wear, liner scuffing and piston ring breakage resulting in serious operational issues.

VPS suggested a number of preventative actions to ship operators using VLSFOs in order to protect engines and avoid operational issues arising from excessive liner wear. Primarily undertaking Cylinder Scrape-Down Analysis to identify if an adequate Lubricating Oil formulation is being used, which may be further confirmed by a Sweep Test. In addition to this, ship operators should closely monitor engine operation during introduction of new VLSFO fuel and fuel changeover procedures.

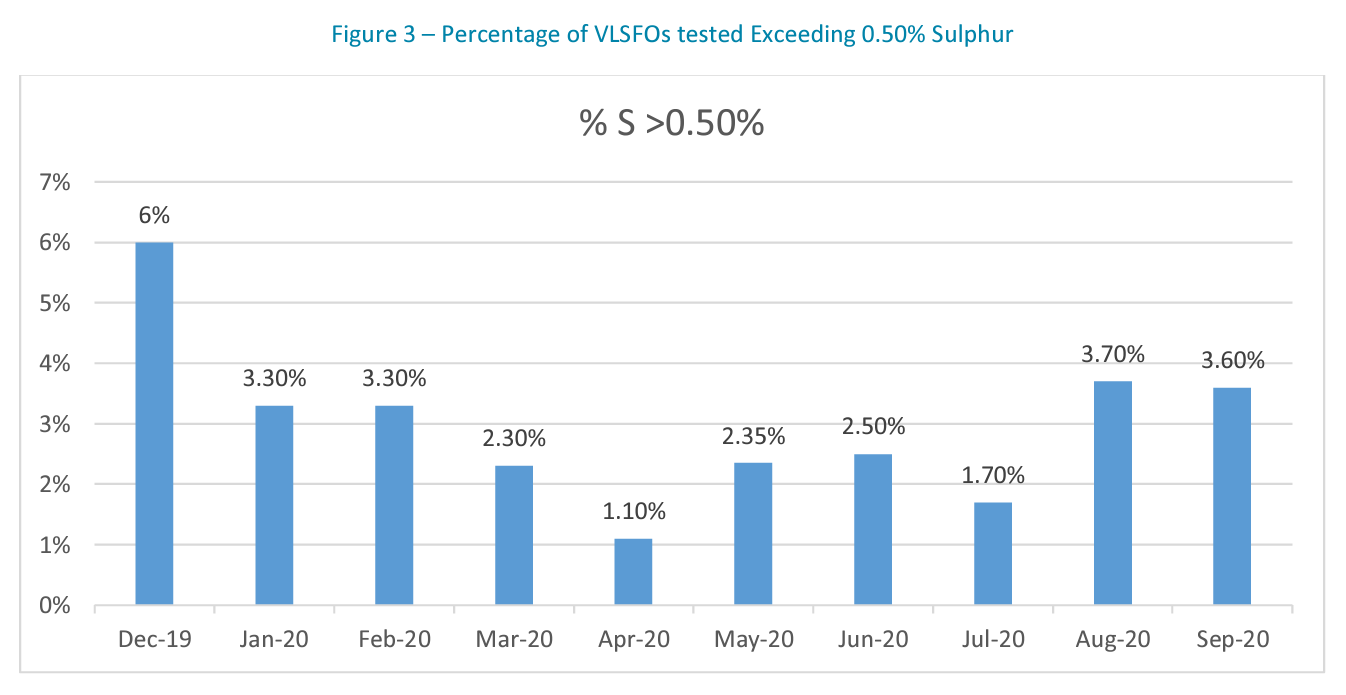

The key reason for VLSFOs being developed was to ensure compliance with IMO2020 and the 0.50% Sulphur global cap limit. However, whilst sulphur levels exceeding 0.50% decreased from December 2019 to April 2020, going from 6% down to 1.1%, we saw an increase in samples tested exceeding 0.50% S from May, with 3.6% of tested samples exceeding 0.50% S in September, (Figure 3).

One good news story relates to VLSFO cat-fines which were expected to be higher for VLSFOs. In January cat-fine levels ranged from 2ppm-500ppm, with 22% of all VLSFOs tested having cat-fines greater than 40ppm. However, these levels decreased throughout 2020 and now the range is 279ppm, with 11% of VLSFOs tested having a cat-fine level greater than 40ppm.

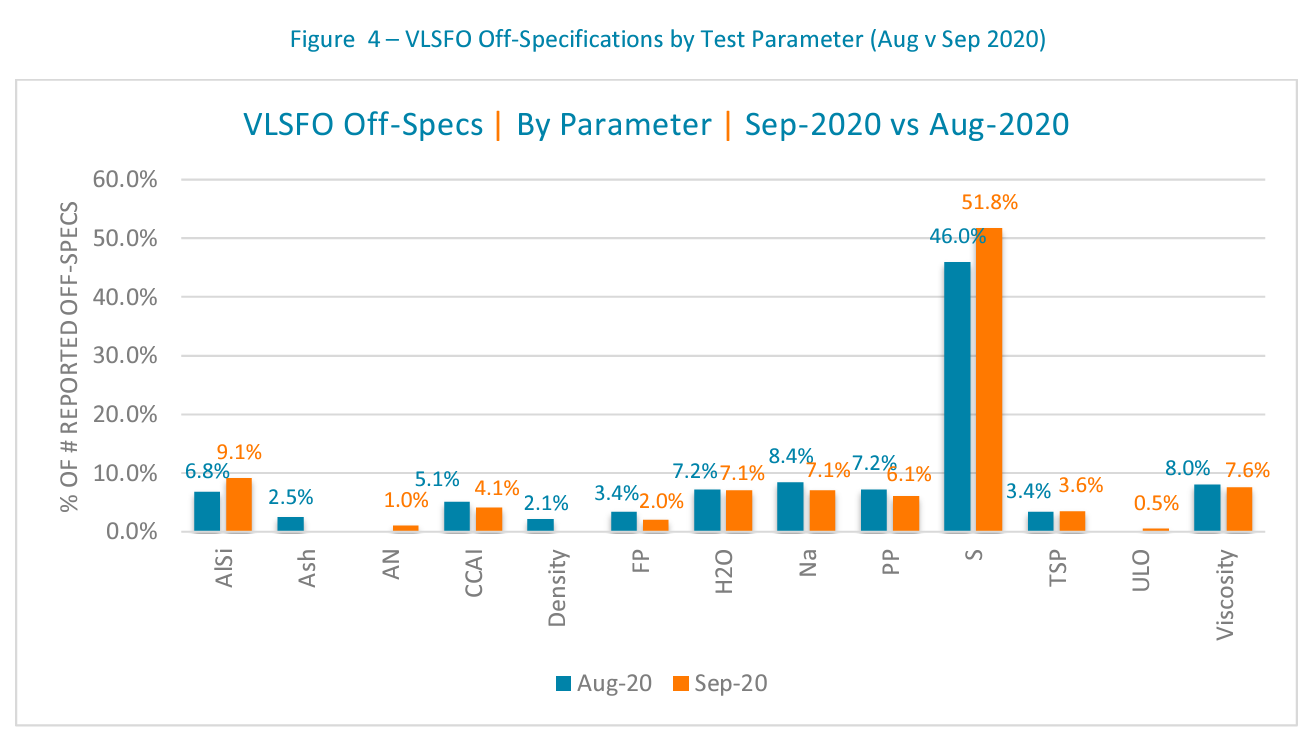

Overall VPS are currently seeing 6.2% of all VLSFOs tested exceed at least one test parameter specification, with ironically, sulphur accounting for 52% of these off-specifications, (Figure 4). In terms of geographical regions, Europe accounts for the highest percentage of VLSFO offspecifications, with 15% of all samples tested from Europe, exceeding at least one test parameter specification.

It would also seem that marine fuels did not escape the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. With a significant reduction in aerospace and road traffic due to the virus, there was a surplus of aviation and automotive fuels at relatively lower price. These fuels have lower in flash points than marine fuels, but also contain very little to zero sulphur. As a result it seems likely that these fuels have found their way into the bunker supply chain. This is supported by an increased number of flash point cases witnessed in MGO, VLSFO and HSFO. Out of the 37 Bunker Alerts VPS issued between Jan-Sept 2020, 17 have been related to flash point issues, with 9 for MGO, 5 for VLSFO and 3 for HSFO. Over the same time period of 2019, VPS issued 8 flash point related Bunker alerts, all of which were for MGO.

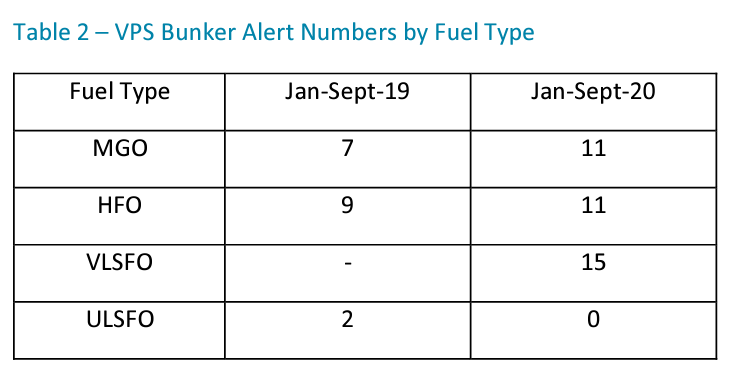

Overall 2020 has given rise to many more fuel quality issues than witnessed in 2019 and again returning to VPS Bunker Alerts as an indication of marine fuel quality, we have issued more than double the amount of Alerts year to date compared to the same time period in 2019. See Table 2:

Looking to the future, the IMO has set targets for the reduction of carbon dioxide and greenhouse gas emissions. A 40% reduction in carbon intensity relative to 2008 levels by 2030 increasing to a 70% reduction by 2050, with a 50% reduction on carbon dioxide levels relative to 2008 levels by 2050.

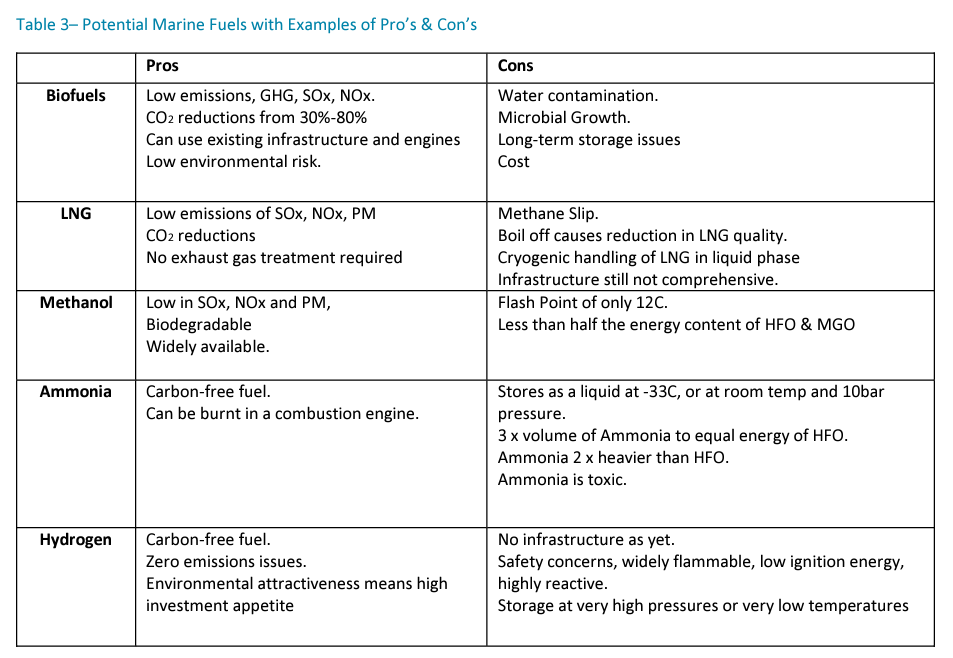

These challenging targets will require the use of fuels with lower carbon content, carbon-neutral and eventually carbon-free alternatives. We already have LNG in use for certain shipping sectors and regions, with methanol also being considered, as another potential option. However, biofuels are gathering higher levels of interest as an alternative fuel.

Some of the advantages of biofuels are: there is no required change in the supply change logistics, no retrofit capex and the fuels can be burnt in existing engines. The source material can be Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME), Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil (HVO), or Hydro-processed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA). Using biofuels made from food crops, may cause future conflict as the humanitarian question raised is, should such crops be used for food rather than fuel? Therefore, using waste materials such as used cooking oil (UCO), or even algae, would be politically safer routes for biofuel production. Biofuels can offer potential CO2 reductions of between 30%-80% and therefore a major step towards the IMO targets, certainly over the next ten years.

However, like all fuels, Biofuels, Methanol, LNG and others such as Ammonia and Hydrogen, being considered, all have their pro’s and con’s and all require sound and proactive fuel management.

Whichever route shipping takes from 2021, we can only hope the future is more positive than we’ve seen in 2020. It is certainly looking as though it will be a cleaner, greener future, than we’ve had in the past.

Search

Search

Customer

Customer